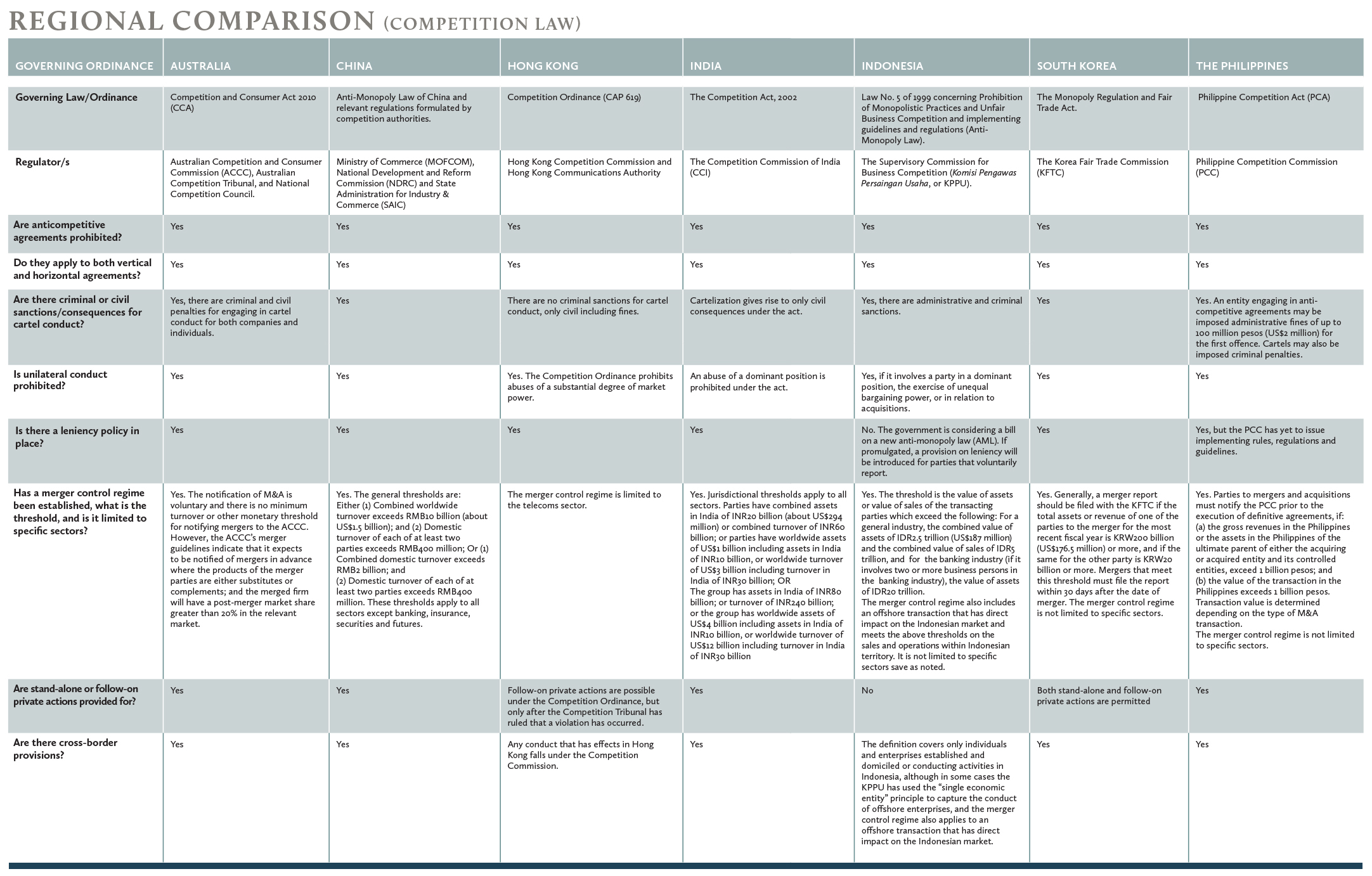

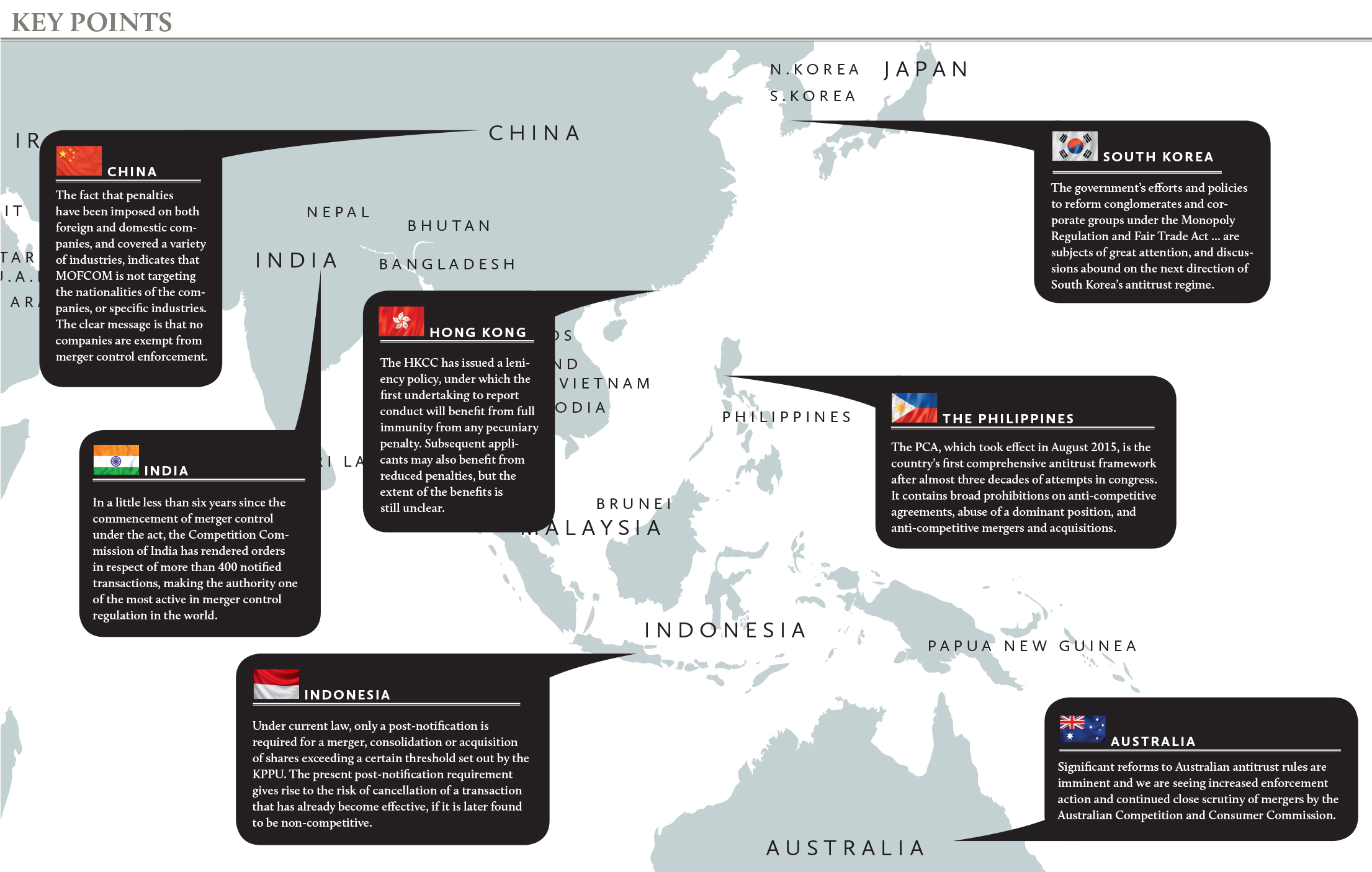

Competition laws within the region are developing rapidly. Clampdowns on abusive activity are more frequent, while enforcement agencies are communicating more across borders to assist their investigations. There has never been a greater need for investors to strengthen compliance and update on laws across the region

Navigation

Overview | Australia | China | Hong Kong | India | Indonesia | South Korea | The Philippines

Navigation

Overview | Australia | China | Hong Kong | India | Indonesia | South Korea | The Philippines

AUSTRALIA

There have been a number of important recent developments in Australian competition law. Significant reforms to Australian antitrust rules are imminent and we are seeing increased enforcement action and continued close scrutiny of mergers by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

In summary, current trends in competition law in Australia include:

- Significant pending law reform, which generally broadens the anti-competitive conduct rules in Australia;

- First prosecutions of criminal cartels;

- Push for higher fines for antitrust breaches;

- Continued close scrutiny of mergers;

- Greater use of market studies.

Partner at Allens in Sydney

Tel: +61 2 9230 3897

Email: Kon.Stellios@allens.com.au

Pending law reform

In 2014, the federal government commissioned a review of Australia’s competition laws (the Harper Review). The government agreed to implement the majority of the review’s recommendations, and in September 2016 released draft legislation, which was introduced to parliament in March 2017. It is expected that this legislation will be passed imminently.

Key reforms

Misuse of market power. Currently, the law prohibits companies holding a “substantial degree of market power” from taking advantage of that power for the purpose of damaging competitors, preventing new entry or deterring competitive conduct. The proposed amendments will remove the “taking advantage” limb and introduce an “effects” test such that a company with a substantial degree of market power will be prohibited from engaging “in any conduct that has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition”.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

MOCHTAR KARUWIN KOMAR OFFICE

14th Floor WTC 6 (formerly, Wisma Metropolitan II)

Kav. 31 Jl. Jend. Sudirman,

Jakarta 12920 Indonesia

P.O. Box 2844 Jakarta 10001

Tel: + 62 21 571 1130;

Email: mail@mkklaw.net

www.mkklaw.net

Navigation

Overview | Australia | China | Hong Kong | India | Indonesia | South Korea | The Philippines

SOUTH KOREA

With the election of President Moon Jae-in and his assumption of office on 10 May 2017, the new administration of the South Korean government has gained fresh momentum with regard to its agendas concerning antitrust and fair trade regulation, as reforming the existing conglomerate (chaebol) structure was a highlight of President Moon’s promises in his successful presidential campaign.

The policy of the new administration is to improve corporate governance structures and strengthen penalties and sanctions for unfair trade practices and corporate crimes, through enactingnew laws and revising existing regulations on corporate groups. So the government’s efforts and policies to reform conglomerates and corporate groups under the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act, South Korea’s principal law governing antitrust and fair trade regulation, are subjects of great attention, and discussions abound on the next direction of South Korea’s antitrust regime, as well as what corporate actions or reforms will be necessary to respond to the latest developments in the regime.

Foreign Legal Counsel at

Barun Law in Seoul

Tel: +82 2 3479 5711

Email: paul.choi@barunlaw.com

Corporate groups

Some of the main policies relating to antitrust regulation of corporate groups that are expected to be prioritized by the government include: reviving a dedicated investigative department within the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) focusing on oversight of corporate groups; heightening thresholds for imposition of administrative fines under the fair trade act, such as administrative fines imposed under the Act on Fair Transactions in Large Franchise and Retail Business; installation of a special oversight committee for large corporations, with emphasis on overseeing monitoring actions such as forced reduction of prices for suppliers, misappropriation of technology, illicit internal transactions, etc.; expansion of the applicability of punitive damages to violations arising under statutes such as the Act on Fair Transactions in Subcontracting; bolstering regulations preventing owners of large corporations and their family members from fraudulently obtaining personal gains from the corporation; and allowing criminal accusations from private individuals to initiate prosecutions of antitrust or fair trade violations (which currently requires the criminal accusations to be filed by the KFTC).

It is expected that the implementation of the above-mentioned policies would require only an amendment of the relevant enforcement decrees. Also, if a special oversight committee for large corporations is installed, such a committee is likely to focus heavily on monitoring and preventing illicit actions of owners of large corporations or corporate groups.

Societal consensus

Furthermore, convinced that there is a societal consensus on the need to curb illicit transactions and dealings by corporate owners and their family members for their own gain, the KFTC announced, in January 2017, that it would enact new guidelines for prevention of illicit actions of owners of corporations and their family members, to set up clear guidelines for regulatory actions against the same.

This calls for corporations operating in South Korea to gain knowledge of the direction of upcoming regulatory changes, particularly since the above-mentioned guideline provides for stricter controls on intra-group support as potential unfair trade practice.

First, corporations may need to consider adjusting the ownership ratio of interested persons in the entity, providing the support to fall below the following threshold and thereby decreasing the potential application of the new guidelines. The current relevant threshold under the fair trade act and its enforcement decree is 30%, or a higher percentage of ownership in an affiliate by a specially interested person for listed corporations (20% for non-listed corporations).

More transparency

Furthermore, the process of transacting with an affiliate should be made more transparent, such as allowing non-affiliate, third-party companies to contend with the affiliate company in a tender offer process to make the transaction more at arm’s length. Even if a tender offer or competition with non-affiliates is not feasible, the terms of the transaction should be that which may be deemed as arm’s-length terms – price, interest, etc. – by the KFTC.

Despite the above-mentioned, however, it is worth noting that other risks may arise even if the process of negotiation was well documented, and if the transaction is of a substantial volume or amount, as it can lead to allegations of undue support, or even the unlawful tunnelling of benefits or profits.

Case law developments

Finally, in addition to keeping abreast of the regulatory changes at the KFTC level, it would also be necessary to pay close attention to the development of case law in the courts with respect to the above-mentioned regulations on illicit or unfair transactions of a corporate group, as the courts may develop their own standards or tests based on the legislative intent of the relevant laws and regulations.

BARUN LAW

Barun Law Building, 92 gil 7,

Teheran-ro,Gangnam-gu

Seoul 135-846

South Korea

Tel: +82 2 3476 5599

Email: contact@barunlaw.com

www.barunlaw.com

Navigation

Overview | Australia | China | Hong Kong | India | Indonesia | South Korea | The Philippines

THE PHILIPPINES

Prior to the effectivity of the Philippine Competition Act (PCA), competition-related laws in the Philippines were widely fragmented. Enforcement of competition laws was assigned to various government agencies and sector regulators. This resulted in an unfocused and ineffective approach in addressing anti-competitive behaviour.

The PCA, which took effect in August 2015, is the country’s first comprehensive antitrust framework after almost three decades of attempts in congress. It contains broad prohibitions on anti-competitive agreements, abuse of a dominant position, and anti-competitive mergers and acquisitions (M&A). It also creates a new quasi-judicial administrative agency, the Philippine Competition Commission (PCC), with primary and original jurisdiction over all matters related to competition, and armed with extensive powers to investigate, issue injunctions, require divestment and disgorgement of excess profits, and impose penalties on companies violating the PCA.

Partner at Quisumbing Torres

in Manila

Email: Christina.Macasaet-Acaban@quisumbingtorres.com

The previous year has seen the PCC, which was established in February 2016, took great strides in carrying out its mandate by issuing the Implementing Rules and Regulations of the PCA in June 2016, working with the National Economic Development Authority in formulating the National Competition Policy, and helping to create a legal and regulatory landscape that enhances competition in the business sector.

Merger clearance

Among the three pillars of competition in the PCA, the PCC has so far focused most of its efforts on merger clearance. This is largely due to the two-year moratorium on the imposition of penalties for anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominance under the PCA, which does not cover merger clearance.

Under the PCA, M&A that would substantially prevent, restrict or lessen competition in the relevant market are prohibited. In addition, the PCA requires parties to any M&A with a transaction value exceeding 1 billion pesos (about US$20 million) to notify the PCC of the transaction, and prohibits them from consummating the same prior to clearance by the PCC or expiration of the relevant waiting period.

Partner at Quisumbing Torres

in Manila

Email: Charles.Veloso@quisumbingtorres.com

To allay uncertainties in connection with M&A that took place after the effectivity of the PCA but prior to its implementing rules, the PCC issued circulars to deal with M&A during this period.

Regrettably, the lack of clarity in the language of the transitory circulars on the PCC’s power to review M&A during the effectivity of such circulars has caused some confusion, and sparked a controversial dispute between the PCC and the two major telecoms players in the Philippines: PLDT and Globe Telecoms. To date, the dispute is still pending in court.

Currently, the PCA’s implementing rules contain detailed provisions on merger clearance requirements, including how to determine the 1 billion pesos threshold that will trigger mandatory notification, and the timing and process for notification.

Despite these detailed provisions, challenges persist:

- There is a widespread consensus in the business community that the pesos threshold is too low.

- As the threshold is generally based on the target’s gross assets or revenues, there are views that the PCC has not considered the market in retaining this threshold. Some businesses have noted that the low threshold would capture M&A involving, by way of example, a floor in a major commercial building.

- While the PCC has acknowledged these concerns, it announced earlier this year that it would retain the threshold, as the same is comparable with those in economies of comparable size, such as Colombia and South Africa.

- The information required in the notification form is too detailed and may entail considerable time and effort to complete, particularly for multinational companies. For example, the notification form requires information on all the entities directly and indirectly controlled by the filing ultimate parent entity (UPE) of each party (notifying group), and any horizontal and vertical relationships between any of the entities within the notifying group of either party.

- The requirements under the PCA’s implementing rules for a binding preliminary agreement prior to filing of a notification, and the prohibition against the signing of definitive agreements prior to the filing of the notification, result in several practical issues for parties. The PCC has issued clarification notes in light of queries that it has received from notifying parties, but the same fail to address the concerns raised by businesses. For instance, until the definitive agreement is signed, parties are not bound by the transaction, and it is not commercially sound to file a notification on the basis of a draft agreement. In addition, until the definitive agreement is signed, a transaction is generally confidential. For listed companies, this gives rise to the risk of leakage of sensitive insider information because public disclosure is generally made only upon signing of the definitive agreements.

- The notification timelines and process for tender offer transactions do not consider the tender offer timelines and process under the Securities Regulation Code. Such a misalignment may have serious implications on the parties and the transaction.

While the PCC has boasted that it has been able to complete its review of all covered transactions within the relevant waiting periods, this does not reflect the period within which the parties complete the submission to the satisfaction of the PCC, and the impact of the entire process on the transaction. - In a recent forum organized by the Presidential Assistant for Rehabilitation and Recovery (PaRR) and Quisumbing Torres, a number of suggestions have been raised to streamline the merger clearance regime of the PCC.

- If the 1 billion pesos threshold will not be increased, the PCC should consider providing a fast-tracked route for clearing filings that may not give rise to competition issues.

- The PCC may consider organizing review teams around certain industries to expedite review and to allow them to build a database of information that would minimize the need for notifying parties to submit detailed information to the PCC.

- Allow the parties to submit a notification on the basis of a signed definitive agreement. This should not give rise to any competition concerns as long as the parties do not implement the agreement prior to obtaining the PCC’s approval.

In the midst of existing challenges in the merger clearance process, and coming to the end of a two-year moratorium period in August 2017, the PCC and businesses will start to focus on the enforcement of the provisions on anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominance.

Questions are being raised as to how the PCA will regulate anti-competitive agreements, considering that, to date, the PCC has yet to come up with more detailed rules and guidelines.

For instance, while the anti-competitive horizontal agreements under the PCA are similar to the prohibited cartel conduct in other jurisdictions, production control agreements and market sharing agreements are not considered as “per se prohibited”. This appears to provide room to argue that production control agreements and market sharing agreements may not be, in some cases, anti-competitive by object or effect.

The broad definition of an “agreement” under the PCA, which includes “concerted action”, may be viewed as covering information exchange and price signalling as a form of anti-competitive agreement.

If so, it is not clear whether concerted action would be punished as a cartel, and subject to criminal penalties, or as among those that fall under the general prohibition against anti-competitive agreements, and subject only to administrative and civil liabilities.

Neither the PCA nor its implementing rules clarify to what extent the same may cover vertical restraints, such as resale price maintenance, non-compete and exclusivity clauses, outside of an abuse of dominance scenario. Considering how certain vertical restraints may have competitive effects and are not uncommon in commercial agreements, this lack of clarity is causing discomfort for businesses.

The PCA’s provisions on abuse of dominance contains broad exceptions for “permissible franchising, licensing, exclusive merchandising, or exclusive distributorship agreements”.

However, neither the PCA nor its implementing rules provide any clear standards to determine when restraints involving a dominant entity may be legitimate, and when conduct is abusive under the same circumstances.

There is also a challenge in delineating the jurisdiction of the PCC vis-à-vis other sector regulators. While the PCA grants the PCC primary and original jurisdiction over all matters related to competition, it did not expressly repeal the competition-related mandates of other sector regulators. Having several regulators review competition-related issues may give rise to inconsistency in policy and enforcement. To address this challenge, the PCC is deepening its relations with key sector regulators through memoranda of agreement, to ensure co-operation, information sharing and policy coherence.

Despite the challenges, the PCC has an opportunity to implement the PCA credibly and effectively. The PCA was envisioned to be a game changer in addressing the challenge of making the Philippines’ economic growth inclusive, and in alleviating poverty and inequitable wealth distribution. However, the PCC will need resources and capacity to fight powerful and well-entrenched oligopolies in the Philippines, while ensuring that its efforts do not deter investment and hinder economic activities.

QUISUMBING TORRES

12th Floor, Net One Centre

26th Street corner 3rd Avenue

Crescent Park West, Bonifacio

Global City, Taguig City,

Philippines 1634

Tel: +63 2 819 4700