Are tweaks to the law enough to achieve parity in the workplace?

The issue of gender equality is being forced up the corporate agenda in India, not least by the new Companies Act, which makes it mandatory for listed companies to have at least one woman on the board of directors. This is a welcome development, but will it result in women being more visible and vocal in the workplace?

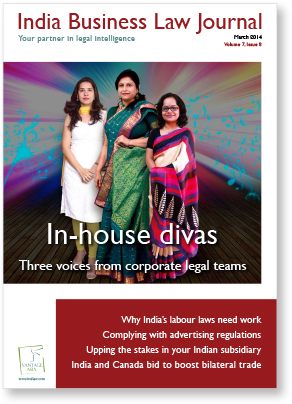

While there is no legislative push for the greater participation of women in the legal profession, it is one area where women are – comparatively speaking – already fairly visible. Some of India’s prominent law firms are owned and run by women, and many others have women in high-profile positions.

Anahita Kumar, who is the director of legal and corporate affairs at Nutricia International, explains: “From police complaints to car accidents, sexual harassment and business dealings. It’s huge and so wide, I really enjoy being part of it.”

If the experiences of our three women lawyers are anything to go by, gender parity in some in-house legal teams may already be a reality. Debolina Partap, the group general counsel at Wockhardt, says that for women like her, gender has never been a handicap. Meanwhile, Sindhu Sankaran, a deputy general manager at Raymond, spells out some of the benefits of having women in senior roles. “We women bring a little more to the table,” she says.

Clearly India will benefit immensely if the Companies Act succeeds in replicating this happy scenario in the country’s boardrooms. It will also be a positive step in the pursuit of greater gender equality in corporate India as a whole.

In Laws that need work we take a look at another area of law that could benefit from a shake-up. India’s antiquated labour laws pose problems for employers and employees in numerous sectors. Our coverage highlights the tremendous struggle that companies face as they grapple with a lack of clarity in the labour law regime.

Employers and employees are not the only people suffering from a lack of clarity. As we detail in Confusing messages, anyone who engages in advertising in India is similarly plagued by ambiguous and disparate regulations.

Advertising is afforded a high level of protection by India’s constitution and courts, yet there is little in the way of a unified framework of laws and regulations to govern the activity. Neither is there a single regulator charged with formulating and implementing advertising policy.

Instead, rules and regulations must be gleaned from a diverse range of state and national laws and regulations, many of which only apply to certain types of product or medium.

Faced with such a conundrum, advertisers are advised to turn to voluntary standards. The guidelines set by the Advertising Standards Council of India are a good starting point for those wishing to play it safe.

In this month’s Vantage point, we turn our attention to arbitration. Palash Gupta, a specialist in the field, argues that a significant judgment by Delhi High Court, in which the court questioned the power of arbitrators to pass interim measures in disputes, will severely curtail the effectiveness of arbitrators. If the ruling in Intertoll ICS Cecons & Ors v National Highways Authority of India stands, an arbitrator’s powers under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act to grant interim relief will be extremely narrow. This, according to Gupta, will force parties to turn to the courts whenever they seek the interim protection of intangible property. He sees this as a worrying development and a significant step backwards for arbitration, which is already struggling to be an efficacious alternative to litigation in India.

While arbitration may be taking a backward step, the international parent companies of many Indian entities are taking a bold step forward. As our coverage reveals (Tightening the reins), a growing number of such companies are seizing the opportunity presented by the low value of the rupee to increase their stakes in their Indian subsidiaries. “The valuations are reasonable and the markets are aligned,” explains Bahram Vakil, a partner at AZB & Partners.

Rounding off this month’s issue, our Intelligence report looks at bilateral trade and investment between India and Canada. In many ways the two countries are well matched: India is a natural market for Canadian natural resources, while for Indian investors Canada offers the stability and certainty that eludes them at home.

The legal and regulatory challenges to investing in Canada have so far proved easily surmountable by Indian companies (unfortunately the same cannot be said for investment in the other direction) and the two countries are attempting to boost bilateral trade to C$15 billion a year by 2015.

Just a few niggles are spoiling the party, one of which is immigration law. As Pat Koval, a partner at Torys in Toronto, explains, the visa systems in both countries present “very real barriers” to investment. “It is not easy for Indian business people to come to Canada at the drop of a hat,” says Koval. “Nor is it easy for Canadians to get to India quickly.”

This may be something that policymakers in both countries should think about if they are serious about hitting their bilateral trade target.